A bouquet is not just a collection of flowers – it is an expression of emotion, style and attention to […]

Flowers In Art

Exquisite still lifes and beautiful plants on canvases: Flowers not only beautify the appearance but also reveal secret meanings and convey messages to the audience. Browsing the fascinating herbarium, in this topic we look at the mysterious picture with symbols of flowers.

Throughout the history of art, certain subjects have resonated particularly strongly with artists and audiences alike. The trends reveal the most popular muses of art, with flowers in the foreground. Rooted in ancient art and still prevalent today, depictions of blossoms, blooms, and other botanical elements can be found in many of the most significant art movements, whether carved into clay or starring in a still-life. Here we will trace the history of the flower in art, exploring its evolution and trends that have attracted artists for centuries.

One of the most popular subjects of Christian art, the Annunciation captures the moment when the angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary that she will conceive a son of God. If you take a closer look, you will find that these scenes almost always feature white lilies. Sometimes called Madonna lilies, these blooms represent the chastity and purity of the Virgin, with their golden anthers signifying God’s heavenly light. Their use marked a sharp turn in the symbolism of the flower, which had once been most closely associated with the fertility and eroticism of the Greek goddess Hera. On the other hand, Christian artists often decorate scenes of the Madonna with the infant with red carnations, which signifies the Virgin's love for Christ and as a harbinger of his crucifixion. Red roses also symbolized Christ’s sacrifice, with each of their five petals representing one of Christ’s wounds from the cross. While these red flowers stood for mortality in Christian art, they carried meanings of earthly love and devotion in wedding portraits of the same period.

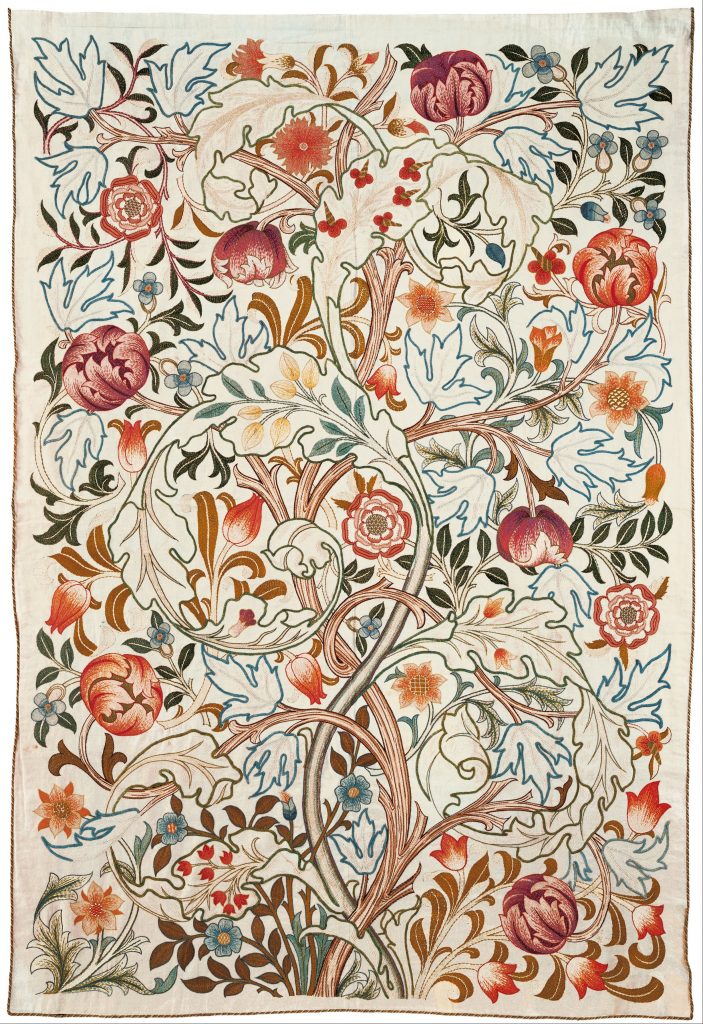

Floral motifs were also prominent in the decorative art of the Middle Ages. During this period, tapestries and other large-scale textile arts gained popularity, appearing in castles and churches throughout Europe. In many of these works, the subjecт, often a group of figures, is placed against a backdrop embellished with repeating floral patterns. These pieces are known as Millefleur tapestries /mille-fleurs/.

During the Italian Renaissance, artists were inspired by millefleur tapestries and often incorporated floral designs into their large-scale mythological paintings. In Primavera by Botticelli, the goddess of Spring is shown sprinkling flowers on the blossom-covered forest floor, which make up most of the 190 blooms featured in the painting.

At that time, many Renaissance artists in northern Europe specialized in still life painting. Often these images include floral arrangements that, according to the Metropolitan Museum, "usually combine flowers from different countries and even different continents in one vase and at a time of flowering," illustrating the importance and distribution of botanical books and other floral studies during the Northern Renaissance.

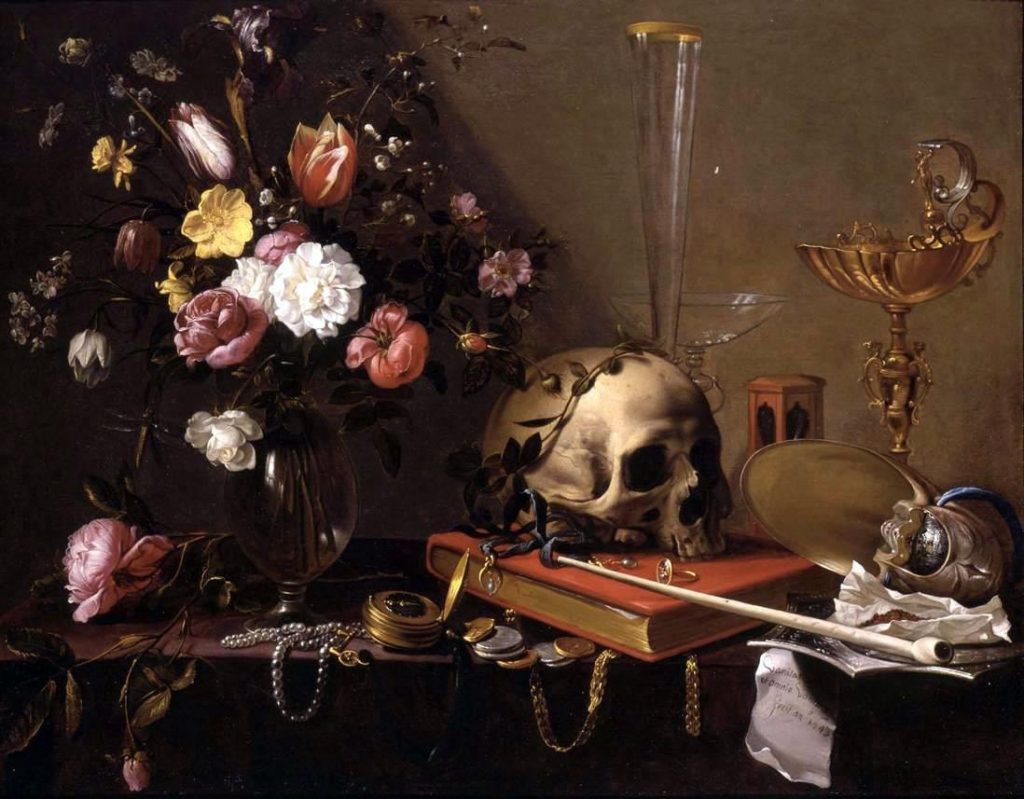

Wilting flowers to capture the fleeting nature of human life

Still life has flourished in the Netherlands since the 17th century, at a time when world trade had cultivated a desire for exotic personal belongings, such as glass cups and tulip bulbs. Among these treasures, Dutch artists create moralizing still lifes that remind viewers of the fleeting nature of material wealth. These works of art often called memento mori ("memories of mortality") or vanitas ("emptiness"), represent skulls signifying death, hourglasses that show the passage of time, and withering flowers that symbolize the ephemeral. Meanwhile, the Dutch are also painting bouquets of fresh flowers to highlight the power of the Netherlands and the glory of nature.

The secret messages of flowers in the Victorian era

Under the reign of Queen Victoria, new standards of etiquette limited communication across England’s upper class, so many began sending secret messages by way of flowers. In turn, books about floriography /the language of flowers/ became popular, outlining the types of flowers that signaled flirtation, friendship, embarrassment, or disdain. For example, you might find that red roses indicated love, darker roses suggested shame, and pink roses sent the message that your love should be kept a secret. In this period of floral fever, British artists filled their paintings with hidden botanical symbolism. For example, in The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicts the tragic story of Emperor Heliogabalus watching his guests suffocate in a rain of rose petals.

Meanwhile, designer William Morris brings the Victorian charm of flowers into the home, creating colorful wallpaper with patterns of poppies, vines, chrysanthemums, and sunflowers.

Symbolism was actively used in art until the second half of the 19th century. You can see a "talking herbarium" on a canvas by Orest Kiprenski. "Poor Lisa" holding a delicate red flower with her delicate fingers. She tells us about her love and destiny.

Against the background of the portrait of Ekaterina Avdulina we clearly see a clear flower standing alone in a glass of water. Its white color is a symbol of moral purity, but at the same time, it symbolizes death. Its petals are falling apart. This is an allusion to the transience of youth and beauty.

The meaning of the primrose varies depending on its color. In a painting by Edwin Long, yellow primroses act as a symbol of youth and love.

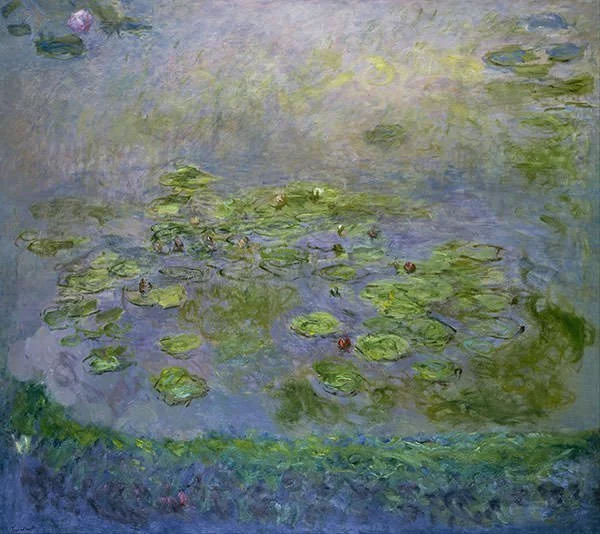

"One moment, one aspect of nature contains everything," says Claude Monet, referring to his late masterpieces, the water landscapes he created at his home in Giverny between 1897 and his death in 1926. Focusing solely on the surface of the lake, with its pile of vegetation floating in the reflection of the sky and trees, Monet creates the image of a horizontal surface on a vertical canvas.

The painting "Ophelia" by John Mile is widely known for its detailed depiction of the vegetation of the river and the plants along its banks. When painting the doomed Shakespearean Ophelia in a lavish scene of death, the artist showed all the flowers with botanical precision, following the text word for word. Each plant is coded with a certain meaning. Buttercups signify ingratitude, weeping willow bent over a girl is a sign of rejected love, nettle is pain, daisy flowers around her right hand symbolize innocence. Roses traditionally speak of love and beauty, and a necklace of violets means modesty and loyalty. Adonis, very similar to a red poppy, swims around the girl's right arm and symbolizes grief.

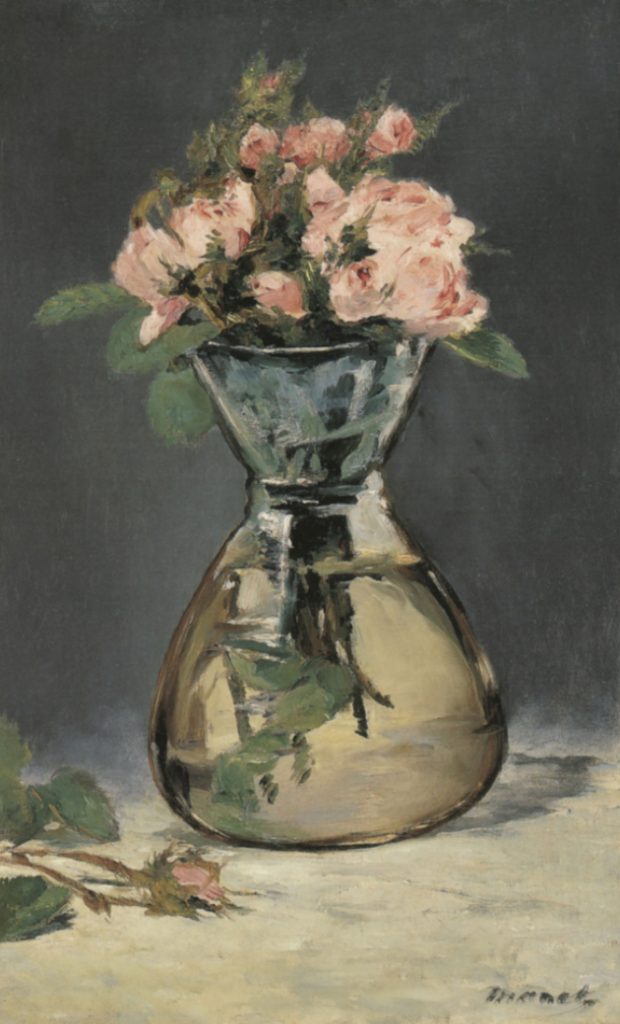

Until the 19th century, floral artists existed somewhere at the bottom of the painting hierarchy. AWith grand history paintings regarded as the most prestigious of all art genres, landscapes and still lifes were viewed as lesser subjects. These distinctions dissipated with the French Realists and Impressionists, who embraced everyday scenes and objects as subjects worthy of art. The French painter Edouard Manet is a leader in this effort and dedicates a remarkable fifth of his artistic work to still lifes. In 1880, towards the end of his life, Manet focused especially on flowers. He created a series of 16 small canvases depicting bouquets his friends had given him on his sickbed and even decorated his personal letters with watercolors of roses and irises.

Like Manet, many Impressionists and Post-Impressionists painted flowers that were personally significant to them. Vincent van Gogh first began painting sunflowers in the summer of 1886 but returned to the subject two years later after inviting French artist Paul Gauguin to stay with him at his yellow house in Arles. Van Gogh created a series of bright yellow sunflower paintings to decorate Gauguin's bedroom, which could be a welcome gesture or a racing trick to showcase his artistic talents. Although originally made for Gauguin, Van Gogh later adopted the sunflower as his personal artistic signature, telling his brother Theo in a letter from 1889 that "the sunflower is mine."

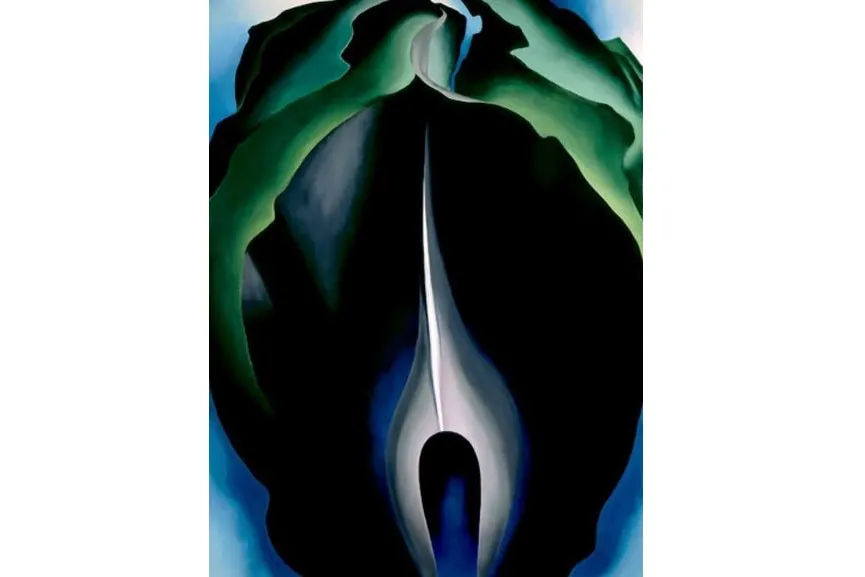

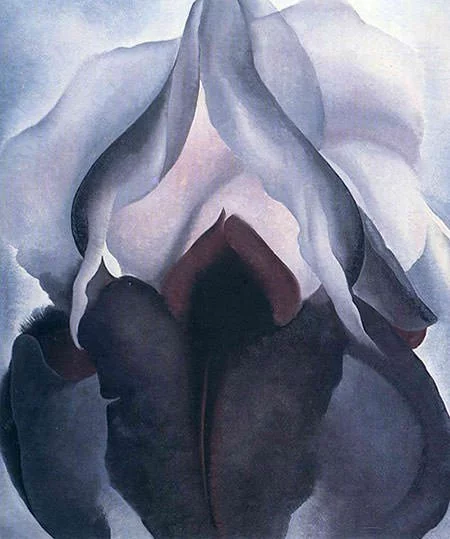

Flowers, given the idea of growth and fertility inherent in nature, have been associated with female sexuality since ancient times. Tamara de Lempicka considered Zantedeschia to be the most feminine and erotic flower and constantly included it in her still lifes.

Critics almost unanimously cite erotic allusions in Georgia O'Keefe's paintings. In 1919, photographer and art dealer Alfred Stiglitz, who later became O'Keefe's husband, first put forward the idea that these floral paintings were in fact images of intimate parts. He sees O'Keefe's work as a manifestation of "eternal femininity." However, Georgia O'Keefe has always argued that her floral paintings have nothing to do with the female body or sexuality, but have been closely related to plant life forms. The lush, symbolic flower paintings of Georgia O’Keefe and the American Southwest are some of the most recognizable works of the 20th century. Often considered the mother of modernism, O'Keefe turns the picture of still life into a radical event. Her close-up views of flowers border on abstraction and challenges viewers to slow down and enjoy the process of careful observation.